In the world of web development, we are currently spoiled for choice in frameworks. And never before I have witnessed quite so many people choosing to forsake the frameworks and build-systems of the past in favor of rolling their own for their websites. And it’s not hard to understand why. Since 2016, React has absolutely dominated the web in one form or another. For all that React does right, it does so much wrong. Whether we like it or not, React pushed the entire web towards client-side rendering (CSR). It didn’t help that the next most popular framework, Vue, was also entirely client-side. It really wasn’t until Next.js began making waves in 2018 that JavaScript developers started to accept Server-Side Rendering (SSR) yet again. (Though lots of other language developers never left it.) And now, we have frameworks like Sveltekit and Next.js (and many others) that support SSR, CSR, static rendering, and sometimes flipping between all three depending on the page. But do developers really understand what they are committing to when picking a rendering style? Or are we all just building websites with Next.js and Vue because that’s what we were told to do?

What are the common rendering strategies?

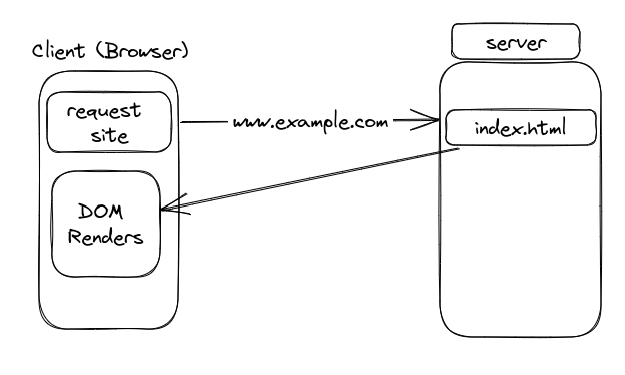

If you understand rendering strategies already, you’re probably okay to skip ahead. For everyone else, let’s give a quick recap on how the web works: user opens browser, user types in your URL, a server reads the URL and serves back an HTML document, the browser renders that HTML document to the DOM, and then that is the web page that the user sees. When an HTML document comes with pretty much all the content already on the page and it gets rendered to the DOM without a lot of manipulation we call that static rendering. It is static because the HTML documents that make up the site are not changing when the user requests them. There’s no manipulation of them on the server or client-side.

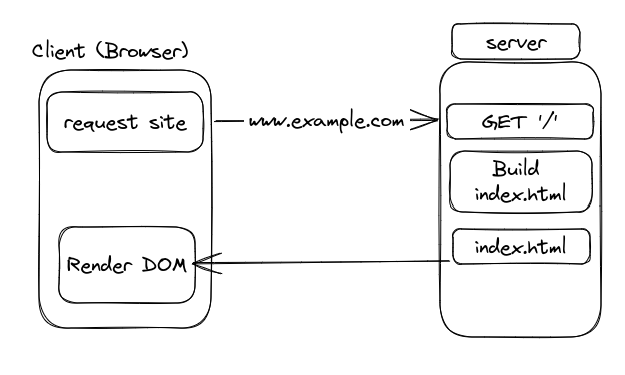

However, just imagine you are an online store owner and you need to make 500 product pages. It seems pretty silly to make them all by hand. It’d be better if you had a database of information and then just had an HTML template you could put that data into as the user requests it and then serve that on demand. This was called server-side rendering.

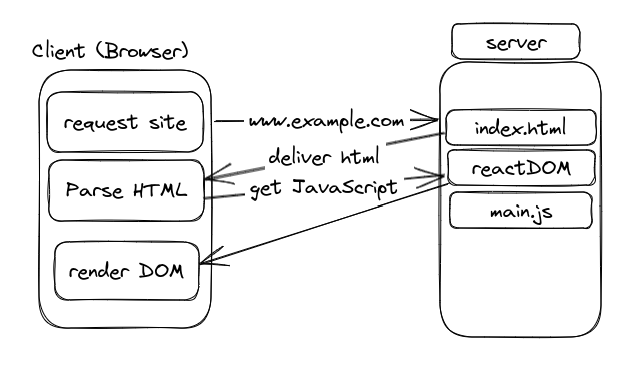

Now imagine you are Facebook in 2010. Everyone is accessing Facebook through their new mobile devices. Server-side rendering timelines and profiles is okay, but mobile internet is slow. Sending a new HTML document that has 90% the same information as the last one you sent doesn’t make a lot of sense. It’s a waste of compute power for the servers and internet providers. It’d make far more sense to send a single HTML document and build the entire site using DOM manipulation with JavaScript. This way, when a user visits two different profiles, you only retrieve the information that is actually different. This is called client-side rendering.

While we are creating three distinct rendering styles, there’s probably more overlap than you might think. For instance, static rendering mostly uses templates these days and just builds hundreds of pages on the server. Server-side rendering usually includes a caching feature where static content is stored and ready for the next user that requests it. Client-side rendering usually includes more HTML templates these days then it did in the past. And there are even more interactions than that, but for right now, let’s take these strategies at face value.

How to define web performance?

Website performance is honestly pretty easy to measure qualitatively. If you go to a website and it loads fast and you can interact with it fast, you generally have a pretty good opinion of that site. Google has done a lot of work into quantifying these user experiences. Google’s Lighthouse is an example of a performance diagnostic tool for the web. In fact, let’s be honest, it is the performance diagnostic tool for the web. Lighthouse attempts to measure all those things that a user cares about. For instance, it measures how fast it takes for the largest piece of content to load, how quickly the screen shows something, and the time it takes for the site to have interactivity. This isn’t an article about general performance per-say so I’m not going to get into the nitty-gritty right now. But if we sum up what users are looking for it’s speed. It’s the speed of how fast do I get the content I came to the site for and it’s the speed of how fast I get to interact with what’s being shown to me.

Beyond users, there should also be business considerations for performance. For instance, computations on servers aren’t free. Serving pages isn’t free. Database calls aren’t free. Maintaining a lot of infrastructure isn’t free. Being able to update marketing information and analytics without engineers is a big deal. There’s a lot to serving your website to the world. However, like all things in engineering, you have to have a balance of having a good website that users enjoy using and having a business that makes money.

How do we decide then?

Okay, so let’s get to my main thesis of this post: how can we decide when we have so many choices and so many things to balance? I want to go through a number of considerations for each rendering strategy and talk about the trade-offs with each. I am mostly going to be looking at this from a high-level performance point-of-view. I’m also not going to look at differences between frameworks. I want to keep this at the highest level of examination.

1. The Building Process

So before we can even begin to talk about serving a site to the end user, let’s talk about how a site is built so that it can be served at all. I’m not talking about development here, I’m only talking about the actual bundling from code. Development is something else entirely and honestly has different business considerations all together.

In terms of building, pure old-school static HTML definitely wins. There is no building. Static site building should be as easy as creating a new HTML document and uploading it to a server. But we don’t live in rainbow land do we? It’s cute to tell ourselves a lie that, “Oh yes, I will create a website just using HTML documents.” However, the reality is that most websites that actually want to make money aren’t that small. They need to be maintained, they need content from marketing, they require a repository of static images, they have components and components have styling, and they have forms that need to be connected to your Salesforce. The reality is that most static sites are built with a framework. And chances are, you can’t use your own computer to build it. You probably have to build it on the cloud in a pipeline of some sort. I will say, most static sites build really fast and really easily. However, the reality is you are probably looking at some sort of build time.

Client-side rendering is unique because instead of building HTML documents, you are going to be more concerned with the JavaScript library you are shipping. You not only have to ship the runtime for the framework you used, but also all the code you wrote to render anything. Some large CSR websites can have JavaScript bundles so large that MP3 players from our childhoods wouldn’t be able to hold them. It becomes all about making JavaScript as efficient as possible. The build process might include minification, code-splitting, tree-shaking, and transpilation. Honestly, I think most people I know really struggle with understanding how bundling works and the processes in it. I have seen engineers ask why they even have to do it and ask if they can get rid of it. And just like static-rendering, you probably are going to be dealing with a remote pipeline to do it for you. However, there is no getting around the build process with CSR. A lot of frameworks use JSX which has to be compiled before it can be run on the frontend. And if they don’t use JSX then they use Svelte or whatever Vue calls its UI files these days. If you’re doing CSR, you’re just going to have to deal with a build system. There are definitely ways around it in static, but you are stuck with it on CSR.

Server-side rendering is hard to give a good summary of because you can do it with almost any programming language: Golang, Rust, PHP, Python, Java, Node, and, well, just - insert your favorite here. They all can do it. So really, the build step is going to be the compilation of that code. So there is compilation, but usually it is way better defined than JavaScript bundling. However, one thing we do have to consider is that unlike CSR and static rendering, SSR pages are not built when they are put on the server. They are only built when a user requests the document. The server then has to build that page on demand. Well, what if you setup your cache wrong or simply have no cache? What happens when hundreds of users request the same page? You better hope your server has good throughput. More than any other rendering style, SSR’s are vulnerable to server-side performance degradation due to too many requests. Caching usually will save you, but I will cover why we can’t always rely on it later.

In terms of building a site, I really think that static is best. I had to provide somewhat a negative narrative to balance it a little. But overall, static rendering is super simple and you really don’t have to consider too much when you do it. SSR is also great, but the on-demand rendering can be a bit of a double edged sword. And while I personally am comfortable with bundling systems for JavaScript, a lot of engineers really hate them. It’s also much harder to balance the performance of a CSR during the build process. It takes talented engineers to perfect configurations for that.

2. Content injection

Now, if we are talking about content, lets ignore static strings for now. Any of the solutions will be perfectly adequate for rendering static strings. There’s no need to think about it. Same with images. Images really won’t change between the three. I’m talking about remote content that needs to be added to a page. For example, how do we get product information on our product page?

Since pages are built on-demand for server-side rendering, typically the information you need is just taken from a database and injected to the page before it is sent to the user. That is really efficient. The user notices almost nothing except a very small increase in the time to fetch the next HTML document. As far as performance goes, it really comes down to the database performance or wherever you are retrieving it from. But, it is important to talk about caching again here. A page that always changes can’t be cached. If you have a website where you are injecting data that mutates every day or even every week with millions of variations, you might want to consider a different strategy. The problem is that if the data changes, the cache is invalidated. It also might be a problem if a single template handles thousands of pages. You can’t cache all of them so you need to prioritize the ones users are visiting the most.

Browsers are single-threaded in their runtime and have a really slow data fetcher. If you race a browser fetch against a Go or Rust client HTTP request, the browser usually is like 2x or 3x slower. That is a problem for CSR frameworks because they rely on retrieving information from servers that tell them what to render. And those milliseconds can add up. If I’m car shopping and start to open 50 tabs for cars I like, a CSR framework with a fetch time of 200ms will take over a minute just to retrieve information collectively. Meanwhile, an SSR framework might take closer to just under a minute and probably less if the resources are cached (data in this case, not the page itself). And beyond just having to retrieve content, CSR’s also usually rely on needing to also make calls to get additional JavaScript. That just ties up the main thread even more because it has to compile JavaScript and run it and also get data and then put that in the JavaScript. If you are using a CSR framework for really heavy content driven websites, you have to make sure that you have great data bundling.

Static rendering on the other hand can really have the strengths and weaknesses of both worlds. On building, static sites can take in remote resources and use them to build static pages. That’s great because there’s no need to render data on demand for users. The nice thing about static and SSR is that they also both can use the browser fetch to get data that changes a lot. It might not have great performance, but it is better than having a million pages to cover user profiles on your site. The biggest problem with Static rendering and injecting content is that in order to update content, you have to rebuild the whole site. This isn’t going to work for teams that are updating data often.

3. Time to first contentful paint

Google has used the phrase first contentful paint to describe the first time a user sees something on a page. We aren’t talking about their exact definition here, but rather just adopting the phrase to describe when the user first sees your web page. With most modern frameworks, this is pretty fast. It’s usually around 100-500ms even for very large sites. That is because most frameworks these days ship at least some HTML. HTML renders super quick. The browser gets it and shows it.

I don’t think we need to go too much into this one. I think we all already know who wins. Static rendering and SSR frameworks ship HTML to the user. The user is going to see your site load really fast. CSR frameworks ship with a very small HTML but have to compile the JavaScript included with it and then write a whole DOM and then the browser shows that DOM. Now, of course, most CSR frameworks break up the rendering part so that it doesn’t block the main thread and goes from top to bottom. The user might think the whole page has loaded when really just the top portion has. Even still, CSR frameworks really aren’t that far behind in rendering speed. Especially modern ones. If you are talking about Svelte, Vue, Qwik, or Solid, they render almost as fast as HTML documents do.

Rendering, however, can become a huge issue if the DOM is sufficiently large. For instance, I once played around with using Svelte to render all the words in the English dictionary. With such a massive list, the program would be stuck loading for seconds. But, if you do the same thing with SSR, it becomes significantly faster. Bigger DOM’s favor static rendering and SSR.

4. Time to first interaction

I could probably write a very long and mostly naive post about hydration, but I will try and show some brevity today. When shipping a static HTML document with JavaScript there is kind of a trade-off between fast rendering and interactivity. The page will render fast. However, just because the page renders doesn’t mean that you can click any buttons and have them work. In order for the buttons to work, you have to add the event listeners to them. The way you add event listeners to them is with JavaScript all the way at the bottom of your HTML document. What if your document is really long? What if you have JavaScript and CSS that is blocking the full rendering of the HTML document on the main thread? This is a huge source of trouble for SSR and static frameworks. The reality is that framework maintainers are fighting against the terrible third-party plugins that website owners add to their page. They include a 500kb analytics script that isn’t even used in production. However, the main thread has to compile that before rendering the page all the same. And to fight all this nonsense, framework authors have written tons about hydration and how to do it. Qwik has made a huge part of its feature-set dealing with this issue. It’s what Remix claims differentiates itself from Next.

CSR frameworks on the other hand, don’t deal with this to the same degree. Why? Because if you build a page on the fly, you batch all the work as much as you can. You don’t render a component and then later add an event listener to it. You render the component with the event listener already attached. It ensures that when a user sees something on a page that it also has interactivity.

Now there are ways around this. For instance, you could use a web component with your static rendered website. You’d basically mix the best of static HTML and hydration from JavaScript. There are also strategies you can steal from frameworks to hydrate your static HTML.

5. SEO

Most SEO differences between rendering styles are pretty overblown these days. I believe Next still claims in their documentation that pure CSR links can’t be crawled by Google, but Google has been using Puppeteer for a while to render pages. Google also has been tracking user metrics and bot metrics for your site for a while. If they didn’t capture something with their crawler, they have the most used browser that they track all interactions on anyways. I think these days Google has signaled that the most important piece of SEO to them is your performance and your relevance. We’ve nitpicked a lot in this article, but I think you can have good performance with any rendering style. Relevance is up to your marketing.

Now I will say, I have seen examples of this code on sites I audit:

// React code

function Header() {

const [showSubMenu, setShowSubMenu] = useState(false);

function handleClick() {

setShowSubMenu(!showSubMenu);

}

return (

<header>

<button onClick={handleClick}>Submenu</button>

{showSubMenu && <SubMenu />}

</header>

);

}

function SubMenu() {

return (

<ul>

<li>

<a href="/products">Products</a>

</li>

</ul>

);

}Do you see what the issue is? This code is conditionally rendering links in the header. If you are hiding header links, how are SEO crawlers supposed to understand what links are important? And it isn’t like using display: none;. That keeps the link as part of the DOM. But when you do it with state rendering, there’s no way for Google to see your links because they aren’t on the DOM. That’s a pretty big problem for your SEO. Most crawlers can work around it, but the more they have to work to find links, the less important they think the links are. I don’t think this is necessarily a problem with CSR frameworks, but they do make it really easy for engineers to make simple mistakes like this. Sometimes it’s hard to reflect on the consequences of DOM manipulation.

6. Routing

Another thing to consider is routing. When a user navigates to a new page, what happens? For CSR, it usually grabs some JavaScript and data to create a new page. For SSR, it creates a new page on demand if it isn’t cached. And for static, it just serves the HTML document that the URL points to. Performance can be tricky to balance here. While serving a new HTML document might seem fine, a lot of people are out and about and not on home wifi. The other day, I used public wifi for the first time in a while and I was shocked how bad it still is. Waiting for a whole new page to load takes longer than you’d think. In theory, CSR eliminates this problem. If you’ve already visited one user profile on a social media page, you should have that UI cached on your browser. So if you visit a second profile, it should only need some small information to build the new page. This also theoretically cuts down on server expenses since you aren’t sending as much raw code. However, the tricky thing about CSR is that with bad data management and bad bundling, you can absolutely end up in a position where you are doing just as much work as sending HTML files. (It’s part of the reason why Facebook made GraphQL.)

Another annoying thing about routing is authorization. With SSR, it’s actually quite easy because you just check if a user is authorized to visit a page and if they aren’t you don’t serve that page. CSR and static are quite a bit harder to do on their own. Lot’s of people end up just relying on a third-party plugin. Of course it can be done, but it isn’t easy. One big advantage CSR and Static have is that they don’t necassarily require you to write a server. Once you have to roll your own server just to control routing, you lose a big reason why you might pick those over SSR.

Summary

Here is a simple summary of what we’ve talked about:

| Feature | CSR | SSR | Static |

|---|---|---|---|

| Build | Bundling JS can be challenging | Depends on language, on-demand can be an issue | Usually easy |

| Content Injection | Slow content due to browser fetch | Usually faster than CSR | Content is handled at build |

| First Paint | Fast, but not better than pure HTML | Somewhat Pure HTML | Pure HTML |

| Interaction | Interactivity is set at render | Components might be rendered before being interactive | See SSR |

As you can see, client-side rendering does have issues, but it really shines for interactivity and apps where UI is reused a lot. SSR works really well, but tends to have issues if you rely a lot on the server to make millions of variations to pages and have constantly changing data. Static works really well, however, it can’t have dynamic of content by definition unless you do it in the browser and have a data broker.

So what do I do?

There’s a rule of thumb in the development world that answers this question:

- Client-side rendering is for apps like social media and media players.

- Server-side rendering is for websites that create or fetch static content on the server such as a clothing store.

- Static rendering is for sites that don’t change often and have lots of content such as a blog.

So there you go. I think we can see that this old piece of advice still holds true.

I don’t think that’s really an interesting question though. The real question looking into the future will be how do I balance these rendering styles on the same site? We’ve seen it already with Sveltekit and other frameworks. The future of the web isn’t to pick one of these and use it forever on your site. The future is that you understand what pages on your site should be static, which should SSR, and which should be CSR.

Example

Let’s pretend we run a clothing website. On this site we might have a home page that displays a lot of the latest up-to-date information on our brand, we might have informational pages where we talk about the brand or maybe even have a blog, and then we have the product pages and store itself.

Home page

Our home page is going to be the cornerstone of the whole site. We probably don’t want to update the theme or styling very often because we have a stable brand. However, the marketers want to be able to update the images and content pretty often. Usually a clothing site does a release like once a season, so about every 4 months. Being able to update the content there without rebuilding the site or needing the developers is pretty standard. So we’ve already removed static rendering as an option. A home page should be the page where all the links are, the best photos are, and the page is driven by content. It also is going to be one that lots of people are going to visit.

I think a home page just makes sense as SSR. CSR is great at rendering, don’t get me wrong. If you wanted to just go with CSR, you could make it work. However, SSR is really going to shine in this capacity. Also, because this page will be visited by millions of people and won’t change super often, caching works great. You’ll get the benefits of static rendering while keeping marketing happy. Every engineer knows that’s a a win. (Or at least your product manager knows that and is shielding you from when the marketers aren’t getting their way.)

Informational pages

Do I even need to examine it? A brand story doesn’t really change very often. Legal information doesn’t really change very often. Blogs are usually pretty static. Now I think the difference between this being a static render or SSR really comes down to the marketing team. How often are they planning on updating these parts of the website? If it’s often, then yeah, do SSR. If it isn’t very often and they’re okay with it being slow to update, use static rendering.

Product pages

So to me there are two product pages usually on store websites: the aggregate product viewer and the specific product viewer. The aggregate product viewer is the pages with all the products on a page that can be filtered down or searched.

For this one, I really want to break down the ideas because honestly, I’m winging this article at this point. This is real, live engineering happening right now.

- We are probably getting information from a database that should be up-to-date to the second. If a shirt is out of a particular size, we need to know that for the end-user.

- There’s honestly quite a bit of interaction between filtering, or adding something to the cart.

- There’s going to be multiple versions of this same UI. There’s going to probably be a men’s section, a women’s section, a kid’s section, a section for just accessories, etc.

I think you could make a case for either SSR or CSR in this case, but I feel like CSR wins. SSR’s just don’t do a great job compiling on demand information and they don’t handle the necessary interactions super well.

As far as the product pages themselves, I think it also goes to CSR, but only slightly. We want users to have a smooth time shopping for their clothes. Once they’ve loaded the UI for one product page, they’ve loaded it for all of them. The only thing we have to do is send the data. It’s a lot more effecient then sending a new HTML template again.

I will say, the product pages might make more sense as SSR if you were more like Costco. These sites might list a product from another brand. There might be more UI variations between products such that the benefits of CSR are basically eliminated.

Wrap up

I think going into the future we are going to see a web that is driven more and more by route specific rendering strategies. The idea of building websites with just React or Vue is going to seem really antiquated. Instead sites are going to be engineered so that each page is thought about differently. Heck, with things like “island architecture” (have a CSR component on an otherwise static page), we can already see how engineers are mixing rendering strategies on pages.

And even more than raw performance, engineers need to consider users and the business to deliver great websites. Maybe a statically rendered page looks great, but marketing needs to be able to change the header every week. How is that going to work? Do you SSR that? Do you make it static, but make the part that frequently changes a CSR? Do you go all 2000’s with it and add an iframe? Those are the things engineers have to consider. Except for iframes. Iframes have always been the wrong answer.