This is an article I’ve wanted to write for a while now. I haven’t ever been too sure how to present it. I’ve attempted to create tutorials and examples of what I’m talking about, but this is more of a mental model for page performance than an actually practical guide. I’ll try my best to make it practical, but hopefully what you really walk away with from this is a new frame of thought to approach problems from.

Performance is actually a really interesting problem on the web. And it became a really interesting problem because the limitations of the web combined with what customers want from the web are at complete odds with one another. The web is still built as if to be mostly a text document presenter. Yet we can create website apps that design really complex things, present 3D models, shop, bank, stream videos, stream ourselves playing video games, and interact with other people in real-time. The main language of the web is a single threaded beautiful disaster called JavaScript that was never made to do what it is currently doing. (And I love the language dearly despite it’s many, many faults.) A lot of really brilliant people have hacked the web to get us to a place where we can do some really cool stuff with it.

When we write web applications, we have hundreds of ways of doing it now and you may not fully understand what you are instructing the browser to do. That’s okay, most solutions are adequate for most websites. So, in the beginning, you don’t need to understand them. However, as projects grow, the complexity gets turned up and the performance often dips because inadequate guard rails were in place and optimizations were not understood. Managers and coding gurus think they can fix this through enforcing Lighthouse scores or other nonsense before code can be committed. However, I want to give you an architectural understanding of how rendering works so we can think of solutions for our problems.

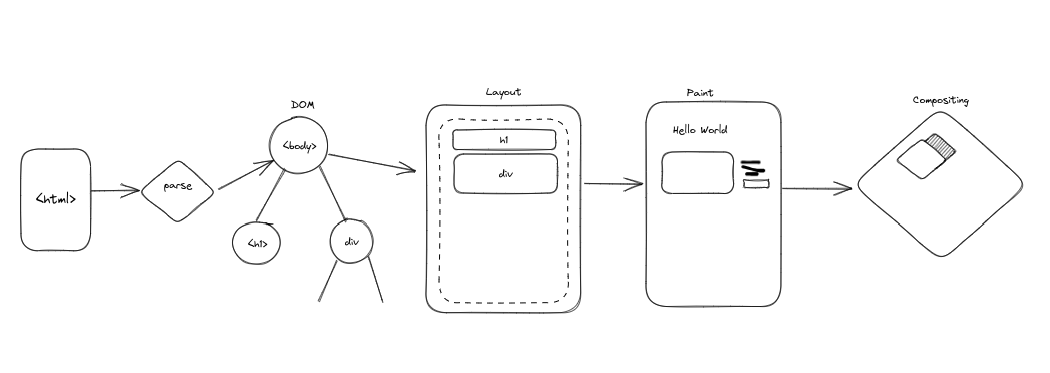

The order of initial render

When a browser receives HTML from a server, it performs the following calculations to build a web page UI:

- Parsing - The browser parses the HTML and CSS to build the DOM tree and the CSSOM tree.

- Render Tree Construction - The DOM and CSSOM trees are combined into a render tree.

- Layout - The browser calculates the layout to determine the exact position and size of each object on the page. (This returns the “box models” for our elements.)

- Painting - After layout, the render tree is traversed to paint the screen pixels.

- Compositing - When components are layered on top of one another (z-indexing, positioning), compositing takes place.

However, rendering only occurs when JavaScript’s tasks, microtasks, and callstack are empty. This is because rendering actually shares the main thread with JavaScript. One way I like to personally conceptualize it in my head is that however many tasks I add to my queue, rendering will always position itself last on the queue. This makes a lot of sense. It’s a waste of time and resources to render when the browser isn’t sure if you are done manipulating the UI.

This can cause some pretty serious issues though if you think about what happens if you have lots non-deferred and synchronous JavaScript. Your initial time to render anything to the page is going to get much longer. Especially if your JavaScript is full of code that doesn’t matter to user interactivity and what the user sees.

There are lots of ways though to manipulate your code such that you don’t block rendering though. Let’s look at some of those.

JavaScript order

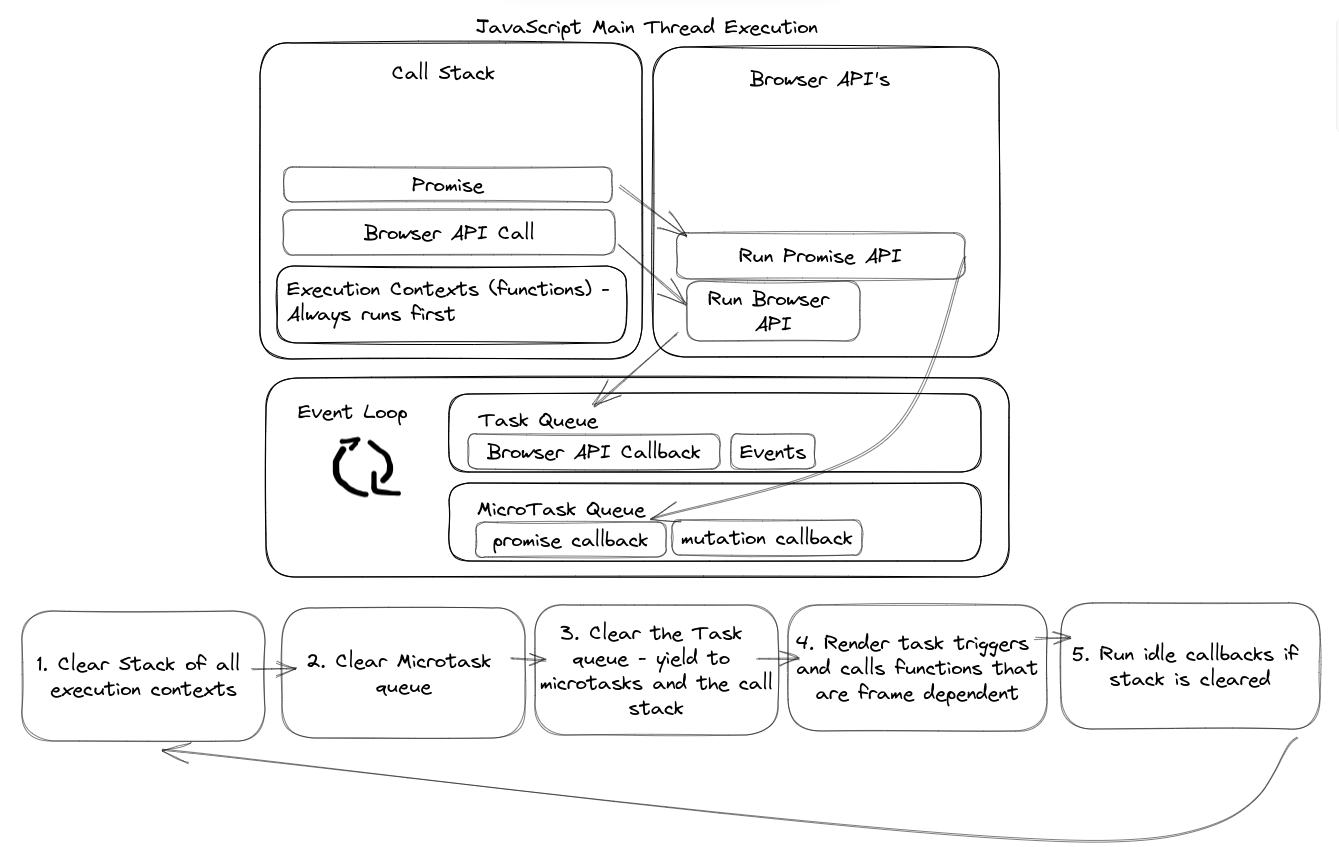

JavaScript has a lot more rules about when functions run than I think most people realize. First let’s just think about how JavaScript is parsed.

When JavaScript is parsed each top-level variable is put into memory for the current execution context. An execution context is can be something like a function or a module. Any where there is code execution and memory. When a function is called to run, it is pushed onto the stack to run.

What some people might not understand is that when an execution context is called the browser considers this a “task” on the main thread. I know it is hard because programmers suck at naming things, but don’t confuse this “task” with Event Loop tasks. These are browser tasks.

So every time we process an execution context we have a browser task. And a browser task runs until the stack is cleared. So it isn’t just the single execution context. The initial function call just starts a task. It runs on the main thread until it is complete. At which point, as long as no more tasks have been queued by asynchronous functions, we will start a render task.

Oh and what about asynchronous functions? What happens with those? Well examining something simple like fetch, it runs in the background in a seperate process until the Promise has resolved. Once resolved, the callback is added to the current stack and run as its own task.

Here’s a summary of execution order:

- Functions that are called within an execution context are added to the call-stack and invoked immediately.

- Functions that utilize browser API’s have their work performed elsewhere and then are added to the Event Loop’s task queue.

- Promise Functions usually have their work performed elsewhere, are resolved on the call stack, and then have their callbacks added to the microtask queue.

- Mutation observer callbacks are added to the microtask queue when mutations are noticed.

- Intersection and Resize observer callbacks are invoked between when the render task performs layout calculations and before painting.

- This is also true of

requestAnimationFrame. requestIdleCallbackwill act only if the browser isn’t doing any critical work. Usually this is only after a render task has been performed and before the next browser task takes place.

Some special considerations you should consider when thinking about how this is all executed:

- Functions that are immediately invoked always have priority.

- The microtask queue doesn’t run until the call-stack is empty. Once it is empty, microtasks are processed until the queue is empty.

- Event loop tasks are run only after the call-stack and the microtask queue are empty.

Example code

Let’s setup a trivial example that shows some of these concepts:

<!-- index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<title>Observers</title>

<script>

const newNodeObserver = new MutationObserver((mutations) => {

for (let mutation of mutations) {

for (let node of mutation.addedNodes) {

if (node instanceof HTMLElement) {

console.log(`element added: ${node.tagName}`);

}

}

}

});

newNodeObserver.observe(document.documentElement, {

childList: true,

subtree: true,

});

</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello World</h1>

<p>

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Exercitationem

animi voluptate tempore magnam nemo minima molestias expedita, mollitia,

numquam sit nobis? Animi quasi praesentium nemo ex cupiditate eum fugiat

iste.

</p>

<ul>

<li>item 1</li>

<li>item 2</li>

<li>item 3</li>

</ul>

<script src="./main.js"></script>

</body>

</html>// main.js

let priorityQueue = [];

let normalQueue = [];

document.querySelectorAll("*").forEach((node) => {

const { top, left } = node.getBoundingClientRect();

if (top > 0 || left > 0 || top < innerHeight || left < innerWidth) {

addToPriorityQueue(node);

return;

}

deprioritize(node);

});

deprioritize({ message: "Hello World" });

processPriorityQueue();

processNormalQueue();

function addToPriorityQueue(node) {

priorityQueue.push(node);

}

function deprioritize(node) {

normalQueue.push(node);

}

function processPriorityQueue() {

while (priorityQueue.length) {

const node = priorityQueue.shift();

console.log(`Node is on screen: ${node.tagName}`);

}

}

function processNormalQueue() {

while (normalQueue.length) {

const node = normalQueue.shift();

requestIdleCallback(() => console.log(node.message));

}

}

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("timeout finished");

}, 0);

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log("promise finished");

});

requestAnimationFrame(() => {

console.log("animation frame finished");

});In this example, we have a top-level mutation observer that watches as the HTML is parsed and adds a logging function to the microtask queue.

We then have an HTML body and a script at the end of it. The script queries all the nodes in the DOM and adds them either to a priority queue or a normal queue. The criteria for this is whether or not they are on the screen during the initial render.

Now, let’s think about that for a second. In order for this code to run at all, there must be a DOM and layout calculations already performed. Because to know if something falls within the original window or not, we have to know the positions of the elements. However, I said above that rendering doesn’t take place until the script has been fully processed. I didn’t lie. The calculations for the DOM and layout were performed, but nothing has been committed to be rendered yet. The browser is waiting to see what the JavaScript does to the DOM before committing. But it built out the DOM and layout as were we parsing the HTML.

At the end of this script I add three more functions, setTimeout, a Promise that resolves instantly, and requestAnimationFrame. Timeout is a browser API, therefore, it adds its callback to the Event Loop task queue. Promises add their callbacks to the microtask queue. Request Animation Frame runs when the browser renders.

So what order to we expect all of this happen in? Well I can tell you first what the console logs out:

- Callbacks from our mutation observer run first. They invoke as soon as the HTML parsing is finished.

- Next our priority queue runs. It is made of simple functions, so they invoke as soon as they are called.

- The Promise callback runs next. It is a microtask so it runs as soon as our stack is empty.

- The timeout callback runs after the promise because it is a task.

- The request animation frame runs because the stack is now empty and the browser has moved to the rendering task.

- The idle callback runs after the initial render because the browser is now idle and awaiting more tasks.

Hopefully if you’re a JavaScript engineer, you’ve seen something like this before in some quiz or some BS “gotchya” interview question.

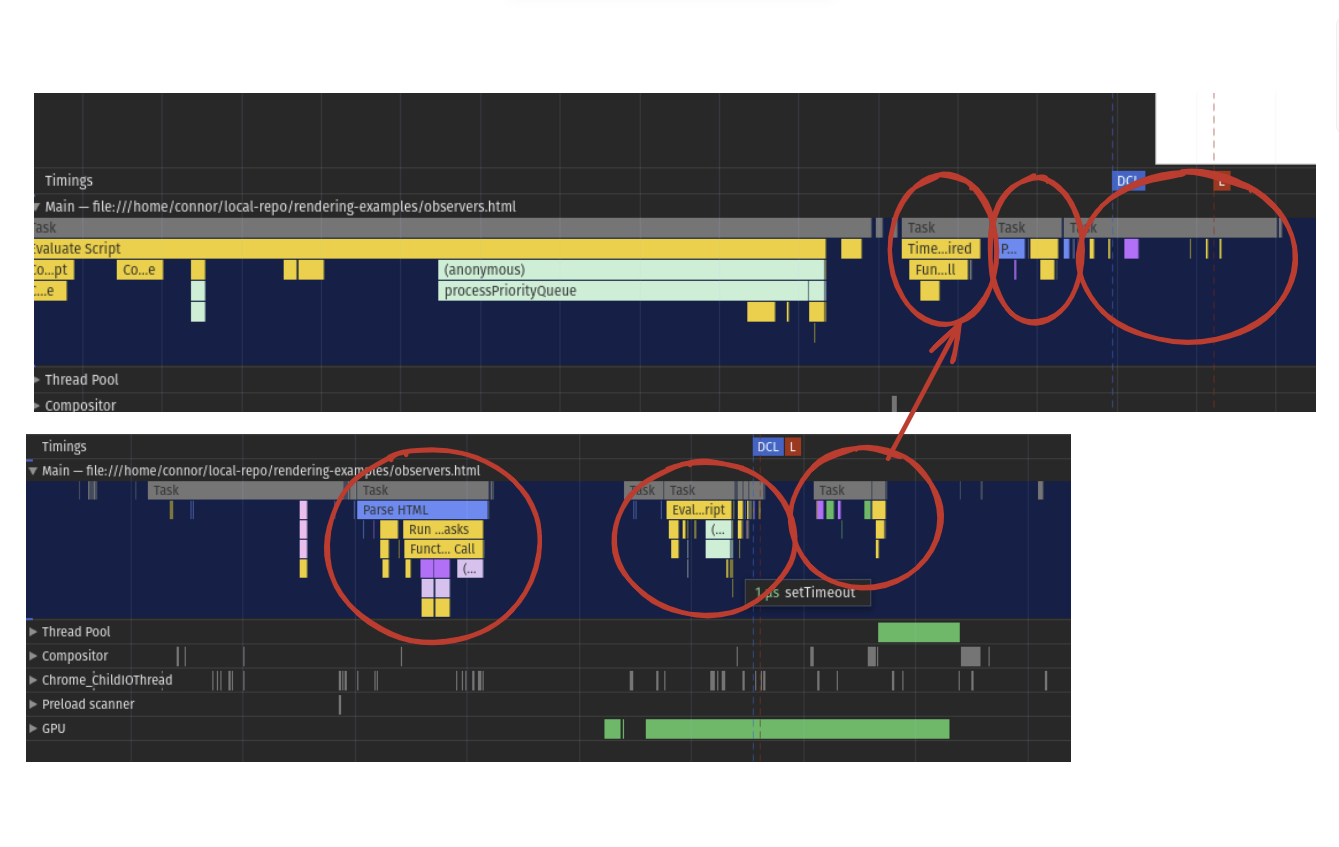

However, let’s go one step further that I feel like gets ignored by so many write-ups of this topic. Let’s examine how the browser actually did this. Open the HTML file in chrome. Go to devtools and go to the performance tab. (There’s also a new performance tab that looks promising, but I’m just gonna stick with the current one.) In the performance tab, click the refresh icon next to the record icon in the top-left corner. The browser is now recording the performance of the page. Go ahead and stop it almost instantly. (The page load should only take like 30ms.) Now you should have a lot of stuff that looks pretty confusing if you’re new to the performance tab.

First highlight the part of the CPU usage graph where you see most of the activity. It’ll probably be like the first 100ms. This will zoom you into that part of the browser process.

Go down to the section titled “Main Thread”. Open it up and you will see a lot of blocks with different colors. This is your main thread (duh) and the blocks represent tasks. Tasks are the top-level blocks and what ran in those tasks are the blocks beneath the top-level blocks.

Let’s talk about each of the major tasks we can see:

- Parsing the HTML - this task is to parse our HTML, however, because we had a top-level script with a mutation observer, we actually created a block of microtasks that had to performed before this task was allowed to clear.

- Running the code - this task runs our script at the bottom of the body. You can see that the

processPriorityQueuefunction is immediately revoked. TherequestIdleCallbackis also invoked, but really what is happening there is that the code is just telling the browser that it has a callback for it to run when it’s idle. - Timer fired task - much like our idle callback, this is actually invoked immediately, but it is just a unit of work representing us pushing the timer callback to the browser API.

- Parsing more HTML? - more HTML is parsed following our script because we never actually finished with the HTML parsing. For all the browser knows, there could be more scripts or whatever underneath this. But you can also see that more microtasks ran at the end of this task. So we can see that the invocation of our Promise was not immediate and did not run on it’s own task. It ran with HTML parsing. This is because there is some Promise manipulation that happens within the browser, regardless of what the promise does. It is returned and then added to the current browser task as a microtask.

- Commit frame and paint - once the browser has parsed all of our code, it renders an initial frame. This frame allows the browser to finish painting the page. Once the page is painted it commits the frame and fires the idle callback. It still takes a few ms for the committed frame to finish rendering for the user, but the process is essentially done at this point. You can see before the paint that there is a function which fires. That was our animation callback.

Practical implications

Now you might wonder, if you’re not a framework author, and you only work with straight forward content-driven web pages, does this really matter a whole lot? I’d argue yes. Understanding this kind of stuff is how you assess solutions. And websites that are supposed to be super simple often have a way of increasing in scope every year until they are a mess and the site owner “just wants to start over”.

However, instead of starting over, what if you just understood what the problems were with the website?

How much blocking of the main thread are you doing prior to page load? How can you improve the feel of your page? How much delay is there between when users see your page and when they can interact with it?

If you need to fetch data before displaying elements on the page, how can you make that as seamless as possible? How can you prioritize hydration of certain components while deprioritizing others?

For instance, look again at our sample. One thing that we did was create a very simple way of prioritizing elements that are already within the window when the page layout is created. Much more complicated versions of this code are used in many different frameworks. It allows you deliver really complex web pages to the user without sacrificing performance.

The other thing that understanding these things allows you to do is assess whether or not a framework or solutions truly works for you. You can see the differences between how React, Vue, Svelte, and HTMX handle re-renders and state changes. It also let’s learn how to use these frameworks in a better way. The most common mistake I see in any framework implementation is doing DOM manipulation or component swapping when a CSS property change works. The CSS property change will likely only trigger a re-paint of the page. DOM manipulation and component swapping not only trigger an entire rendering task, but also probably go through some type of internal work process.

Learning how to optimize web pages is critical. It will make you a better programmer and turn you from someone who just writes code into an actual engineer who meticulously plans and understands the trade-offs made in DOM manipulation.

In the next article, I’ll discuss some advanced hydration techniques that can be used to improve performance on page load.